A new era of discovery: How 150 years of innovation has led to current research that is reshaping health care

Above: PhD candidates, Urvi Patel (front) and Anayra Goncalves (back), working in a laboratory located at LHSC’s Victoria Hospital and Children’s Hospital.

Today’s health care at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC) is made possible by past generations of bright minds who dared to pursue the impossible. Their research has built a culture of innovation, curiosity, and desire to improve outcomes for patients that continue to live in the hearts and minds of today’s scientists, research staff, and learners at London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute (LHSCRI).

Presently, more than 2,300 active clinical research studies are underway at LHSCRI, which is a powerhouse of innovation. From next-generation cancer therapies to world-first diagnostics powered by artificial intelligence (AI), present-day research at LHSCRI promises to reshape the next 150 years of medicine at home and around the world.

Changing the cancer treatment landscape

Cancer innovation has quickly emerged as one of LHSCRI’s strengths. The research institute was one of the centres that took part in investigating a new therapy, called PLUVICTO™, for patients with advanced-stage prostate cancer. The therapy uses a radiopharmaceutical that selectively targets cancerous cells, while leaving other cells alone. As a result of research, the therapy has now advanced to a standard of care with LHSC being the first hospital in Canada to administer a publicly funded dose of the drug.

The research institute also became the first in Canada to use a rare radioisotope (an atom that releases radiation) called actinium-225 DOTATATE to treat neuroendocrine tumours like pancreatic cancer. Led by Dr. David Laidley, Scientist at LHSCRI and Nuclear Medicine Physician at LHSC, researchers are hoping to learn whether this radioisotope, that packs more radiation than standard therapies, is safe and more effective as a treatment option.

In another high-impact project, Dr. Glenn Bauman, Scientist at LHSCRI and Radiation Oncologist at LHSC, and Dr. Timothy Nguyen, Radiation Oncologist at LHSC, demonstrated that radiation therapy called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) is safe even for patients with 10 or more areas of the body that the cancer has spread to. This trial challenges conventional medical limits and may expand the number of patients who qualify for aggressive, yet highly targeted, radiation therapy.

One of LHSC’s most intriguing present-day research pursuits involves enhancing the gut microbiome to fight cancer. In a world-first clinical trial, Dr. John Lenehan, Scientist at LHSCRI and Oncologist at LHSC; Saman Maleki, PhD, Scientist at LHSCRI; and Dr. Michael Silverman, Scientist at Lawson Research Institute (Lawson) of St. Joseph’s Health Care London, are testing whether fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), also known as poop transplants, can strengthen how pancreatic cancer patients respond to conventional cancer therapies. If successful, it could open the door to microbiome-based treatments for some of the world’s most difficult-to-treat cancers. With promising results in other FMT studies, Lawson and LHSCRI are expanding research to more types of cancer.

“London, Ontario is the epicentre of fecal microbiota transplantation research and innovation,” says Maleki. “Together, Lawson and LHSCRI conduct more FMT research across a wider range of cancers than any other centre in the world. Our goal is to improve outcomes for patients with cancer, even those with the most aggressive kinds.”

Promising results help individuals with extremely rare conditions get answers

Rare diseases affect an estimated one in 12 Canadians, yet most of the more than 10,000 known rare conditions are difficult to diagnose because they present with overlapping symptoms, subtle physical features, or genetic variants that traditional testing cannot interpret.

Extremely rare diseases often leave patients and families searching for answers for years, or even entire lifetimes.

Today, an innovative technology called EpiSign helps researchers diagnose rare diseases by looking at ‘chemical signatures’ on a patient’s DNA. These chemical signatures show patterns that can point to specific rare genetic conditions, even when other tests don’t give clear answers. The technology was developed through Canadian collaborations with research conducted at LHSCRI by Dr. Bekim Sadikovic, Scientist at LHSCRI.

This promising technology is especially helpful for patients whose genetic tests show unclear results, unusual symptoms, or no known mutation at all. Getting a clear diagnosis is important because it helps families understand what is happening, get the right medical care, connect with the support they need, and plan for the future.

In 2024, Dr. Sadikovic and his research team found that EpiSign can be used to accurately identify patients affected by birth disorders called recurrent constellation of embryonic malformations (RCEMs). Since their discovery more than 70 years ago, attempts to identify the cause and specific diagnostic markers for RCEMs have been unsuccessful, making it challenging to provide patients and families with accurate diagnoses. This meant that EpiSign could be used to accurately identify RCEMs for the first time using a blood test.

Dr. Sadikovic’s team also used EpiSign technology for the first time to develop an accurate biomarker for a group of disorders called fetal valproate syndrome, which is caused by prenatal exposure to toxic levels of medication that may be used to treat bipolar disorder and migraines, or to control seizures in the treatment of epilepsy. It can result in neurodevelopmental disorders in infants, including learning, communication and motor disorders, autism, and intellectual disabilities. EpiSign allowed researchers to pinpoint an environmental cause for a specific group of disorders.

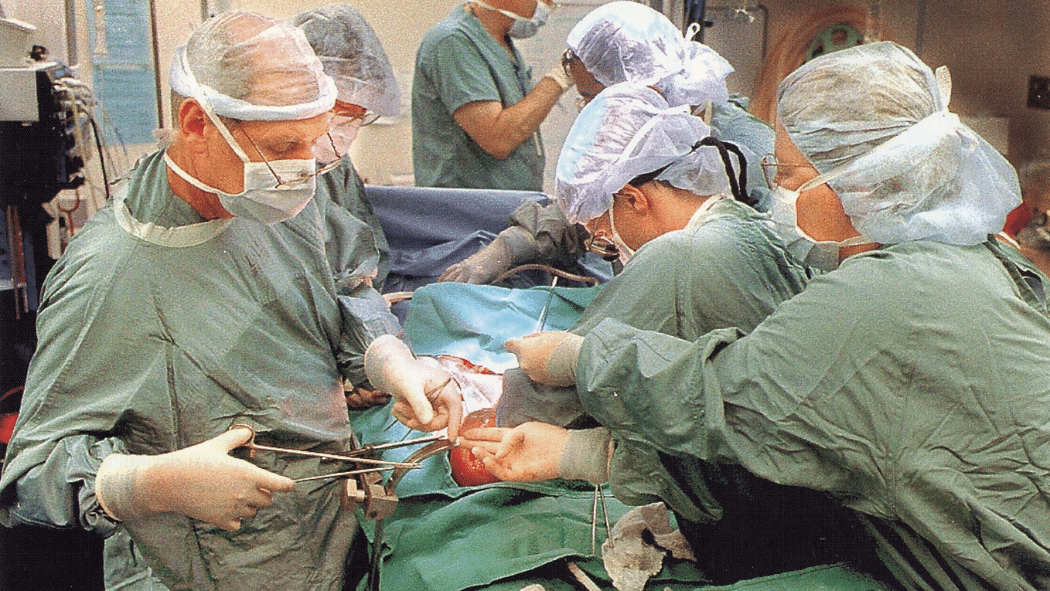

Research in organ transplantation could mean more organs become available and more lives are saved

In another promising study, scientists at LHSCRI are exploring a new technique to make more organs viable for transplant. After circulatory death, when a person’s heart has permanently stopped and blood is no longer flowing through the body, organs can deteriorate quickly and often become unsuitable for transplant. Dr. Anton Skaro, Scientist at LHSCRI and Surgeon at LHSC, and his research team are exploring abdominal normothermic regional perfusion (ANRP) which involves clamping off the area of the organ after death, and recirculating blood only to the area of the organ needed for transplant.

“By making once unusable organs healthy enough for transplant, we can meaningfully expand the donor pool. This is a true game-changer for the field of transplantation,” says Dr. Skaro.

Innovation now and into the future

These examples reflect just a glimpse of the groundbreaking research happening today. With over two thousand active clinical research studies across a variety of research programs, LHSCRI is making an impact on the lives of patients and enhancing the standard of care around the world with new innovative therapies and procedures.

“For more than 150 years, LHSCRI scientists have pushed the boundaries of research,” says Dr. Chris McInytre, Interim Vice President, Research and LHSCRI Scientific Director. “Their work continues to motivate today’s scientists, staff, and learners as they strive to improve patient outcomes. By sharing discoveries worldwide, LHSCRI helps raise the standard of care beyond its walls. This commitment to innovation will carry LHSCRI forward into the future.”