Honoring our legacy: A conversation with a former respiratory therapist

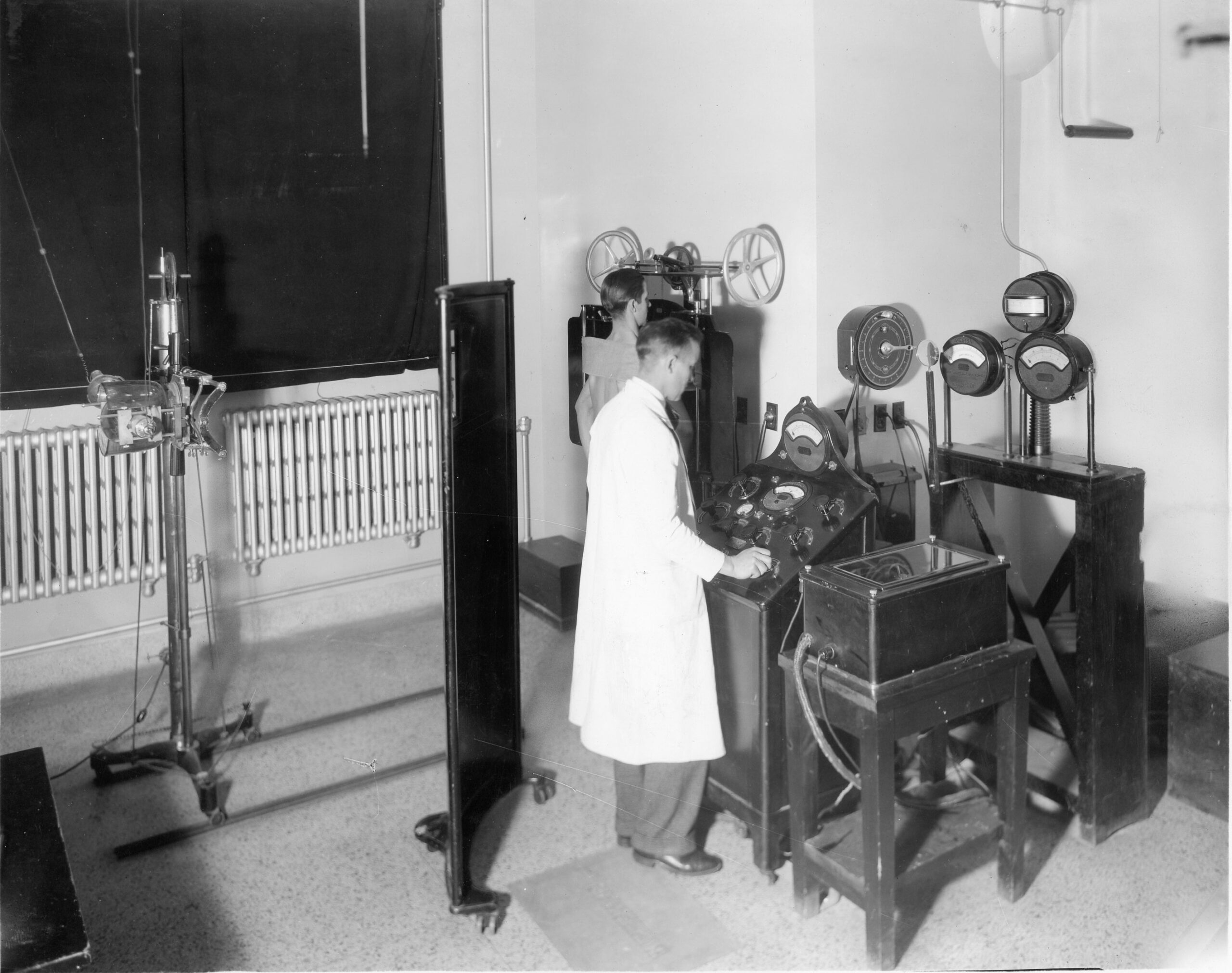

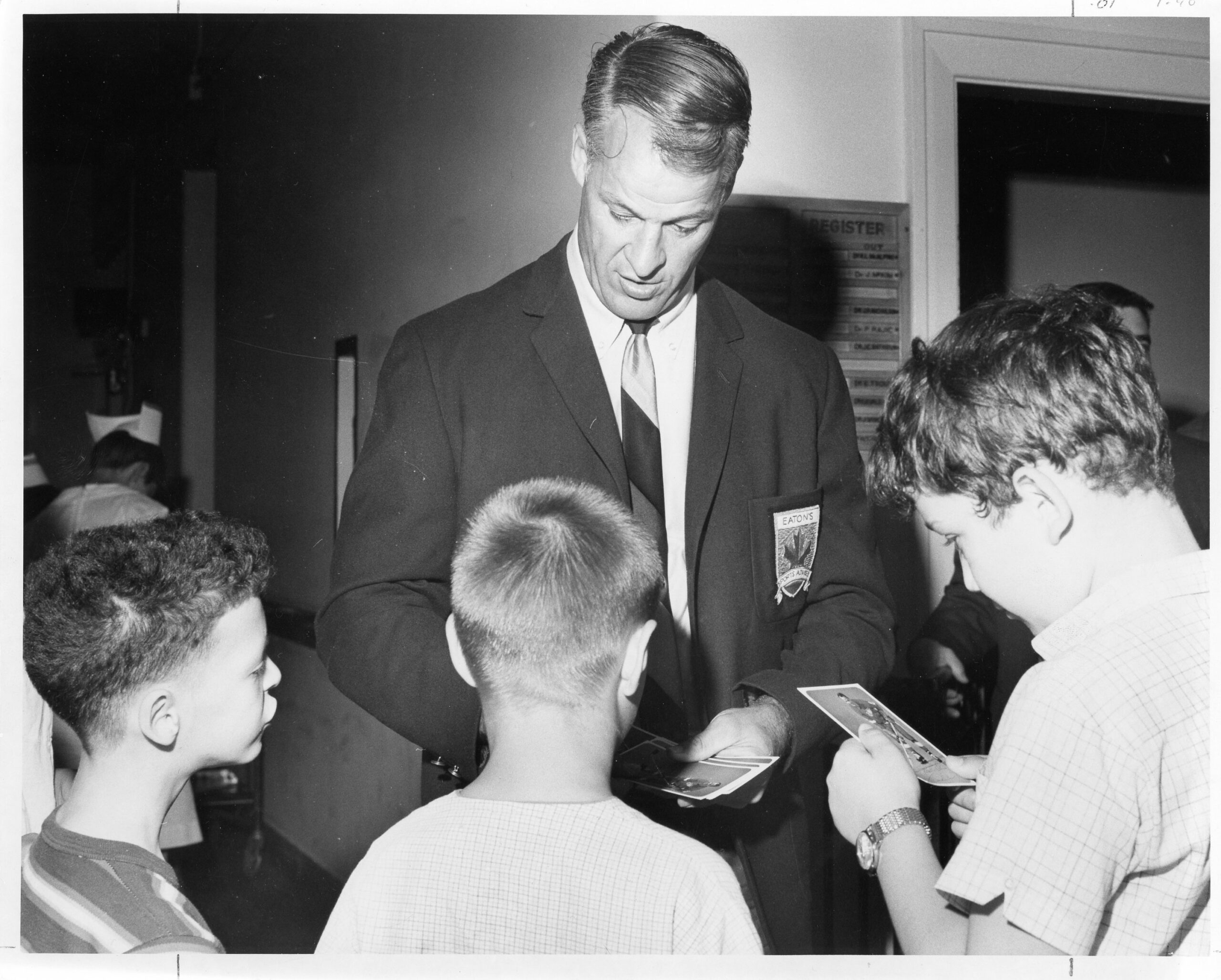

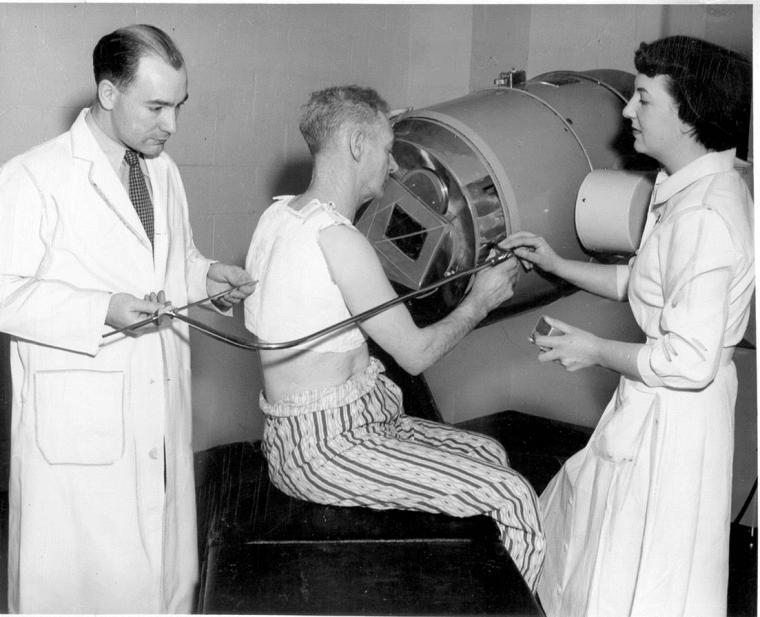

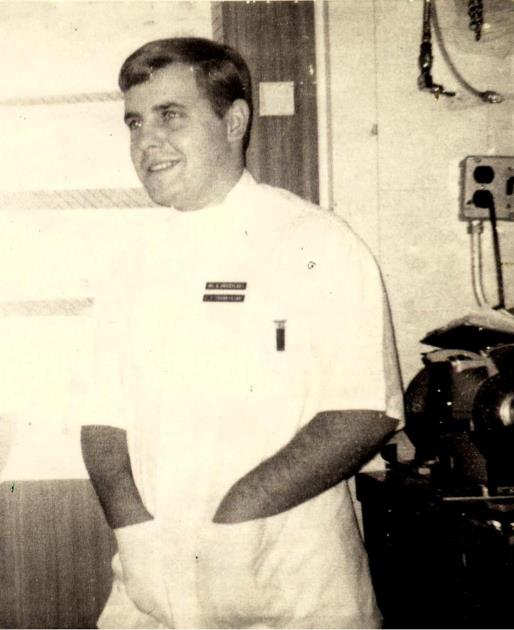

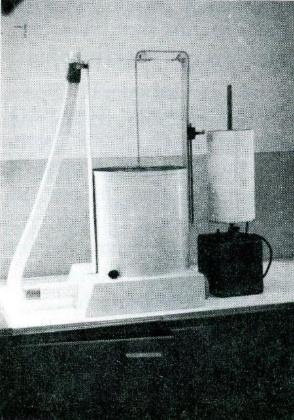

Above: Dave Moczulski pictured at Victoria Hospital in 1967.

Over the past year as London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC) celebrates 150 years, many of the stories we’ve heard have captured the heart of the hospital, including its people, its innovations, and deep commitment to caring for the community. Among those that helped shape our history are the early respiratory therapists. One of them is Dave Moczulski, a former respiratory therapy pioneer at LHSC, whose journey began in the late 1960s and whose memories help bring to life the origins of respiratory therapy at Victoria Hospital.

The story of the respiratory program begins in an auditorium at H.B. Beal Secondary School in 1967, where Dr. Wolfgang Spoerel, Head of Anaesthesia at Victoria Hospital, visited the school to introduce students to a new role he was creating at LHSC – inhalation therapy. His original concept was to create a new clinical support role that included technical skill, patient care, and support in the hospital and a focus on supporting patients with respiratory illness. The field was so new that it had no formal college pathway, no established curriculum, and only a handful of practitioners. Moczulski, straight out of high school, with no medical background, was one of the original six in London recruited to help launch this program.

“Six kids just out of high school and really trying to listen to the terminology and pick up on everything,” he says. “We didn’t know anything about the medical world.”

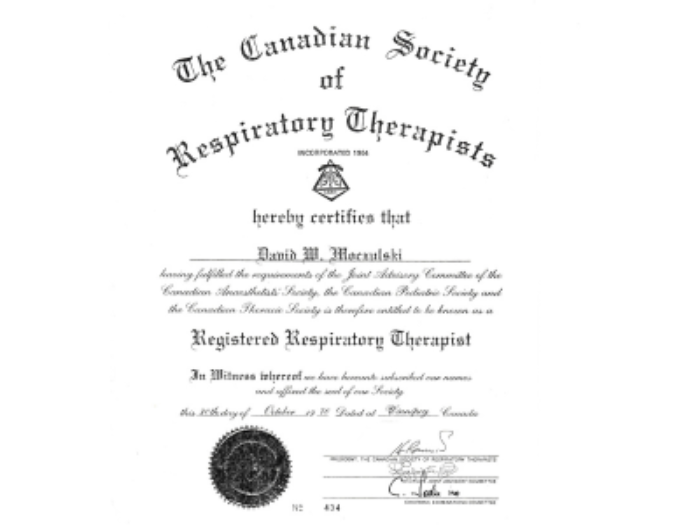

He explains, “Formally, the program started in Canada around 1964, and it was very small at the time. I was the 434th inhalation therapist in the country through this program, so it was very new.”

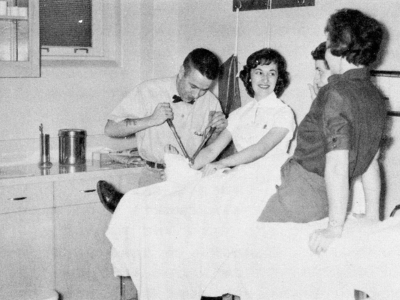

With no standardized training model, the profession was built in real time. Education started with immersive and hands-on work, slowly taking on responsibilities and helping nurses or orderlies with their roles. The education aspect evolved over time through various training institutes and partnerships with other hospitals.

“Two to three days a week, we would be in a classroom,” Moczulski says. “We learned from different sectors of the hospital—medical terminology, anatomy and physiology, and even attending numerous autopsies. The knowledge didn’t happen overnight.”

Their training was supplemented with weekly trips to the Toronto Institute of Medical Technology where they took additional anatomy and medical technology classes and then visited the Toronto General Hospital for more specialized training.

But most of their education happened inside Victoria Hospital.

“Our primary role was technical. Pushing around air and oxygen tanks on cylinder carts, cleaning medical equipment like incubators and respirators… that was how you learned in the beginning.”

Since the role was new, acceptance within the hospital didn’t come instantly. The boundaries of the role were blurry, the responsibilities constantly shifting, and the expectations high.

“We kind of had to prove our worth,” Moczulski recalls. “No one knew us. It was a new role and we were taking on tasks from housekeeping, orderlies, and nurses. We had to show that we could ease their responsibilities and improve patient care.”

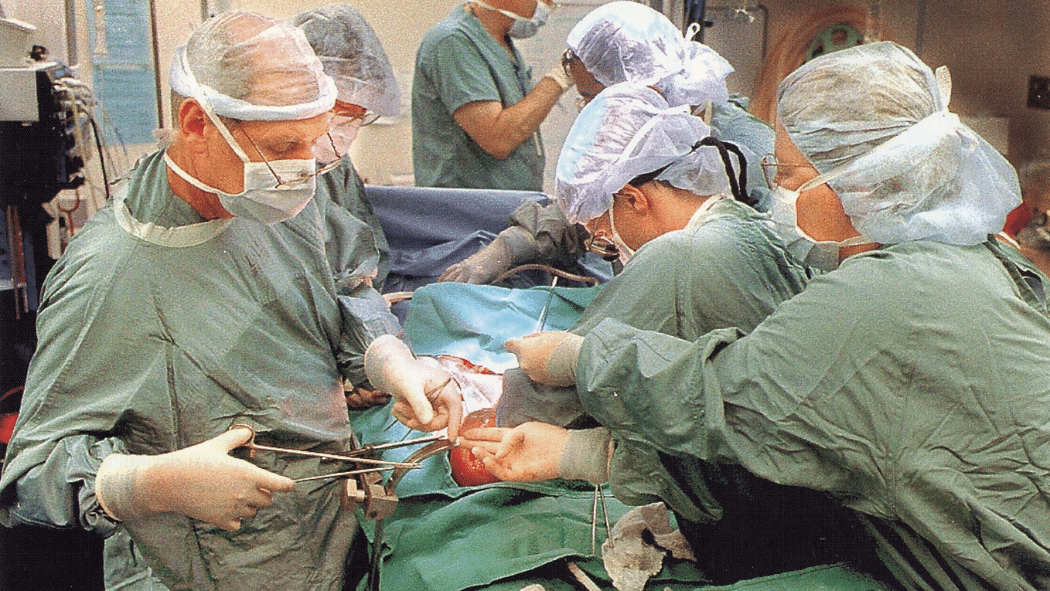

Slowly, the work became more technical, and eventually more clinical.

“We delivered oxygen cylinders and air tanks; we would disassemble, clean and reassemble respirators, test them for operation, sterilize, and then put them back into service for patient use. By the time I left in 1974, they had taught us how to intubate patients,” he says. “That evolution happened over a short period of time.”

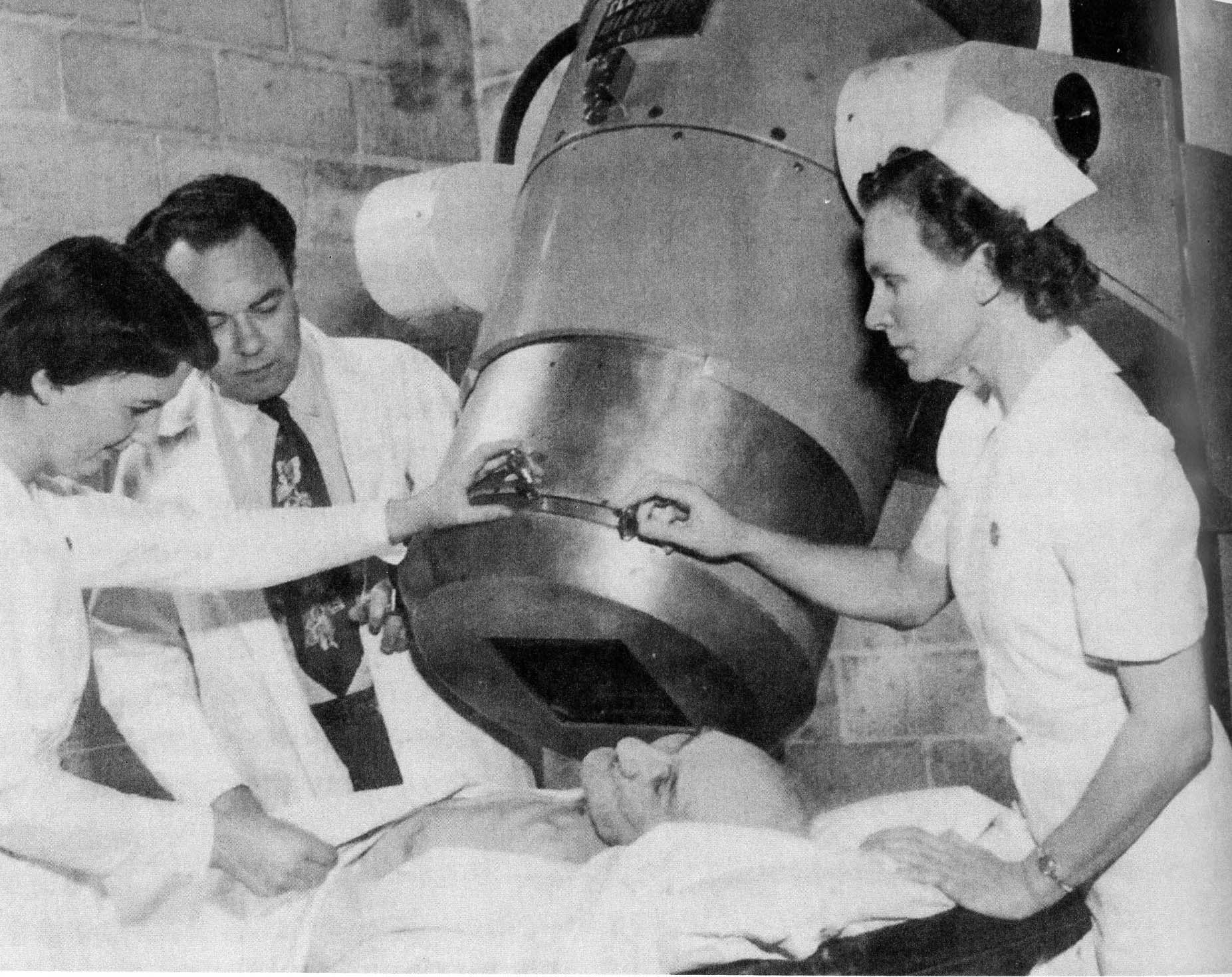

Technology dramatically changed over time and Moczulski saw that change firsthand, starting with the iron lung era to the early forms of portable respirators.

“If you remember the polio days, they used the iron lung. I got to clean one up one time and actually went inside an operating one. They were very large and cumbersome, about eight feet long and weighing about 700 lbs.”

Soon after came “the Bird” Mark seven respirator.

“It was a small portable ventilator that could operate on portable cylinders or attach to the wall oxygen outlet and then attach to a patient’s tracheotomy or intubation tube. It was about ten inches long and weighed about five pounds and extremely portable.”

The team performed pulmonary function tests, provided nebulizer treatments, induced sputum tests, set up respirators, supported the ICU, and eventually became key members of the cardiac crash team.

“We worked everywhere within the hospital structure, always trying to learn,” Moczulski says.

And as the responsibilities evolved, so did the job titles.

“It started off as a gas therapy technician, then changed to inhalation therapy, then respiratory technologist, and then respiratory therapist. The role and responsibilities changed the name.”

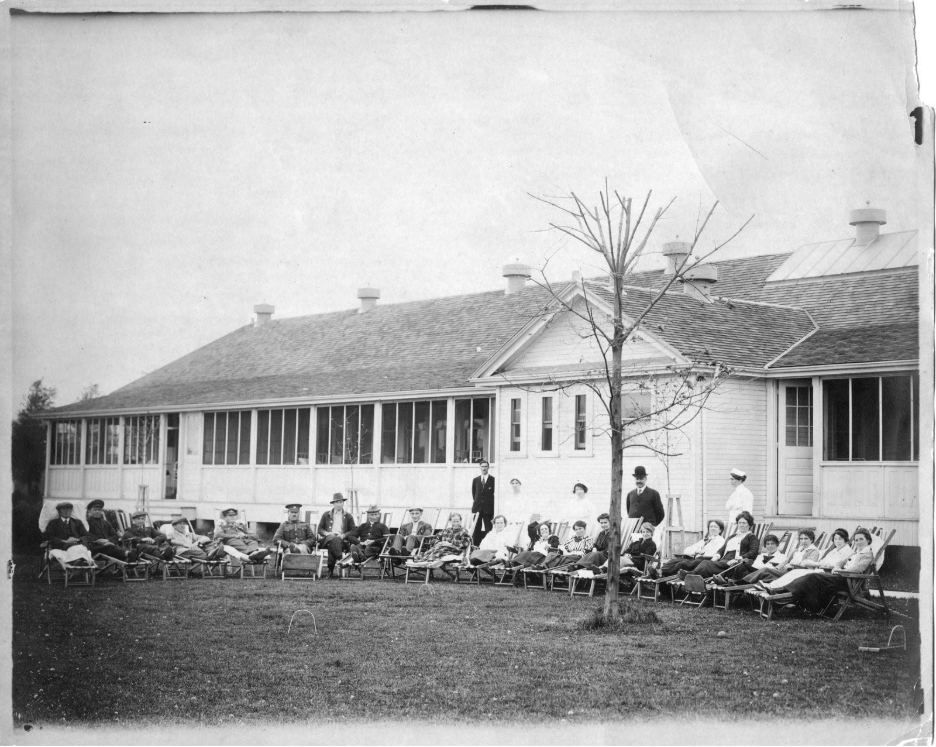

Before LHSC became the regional centre it is today, the hospital landscape looked very different with training and work spread across multiple sites.

“When Westminster Hospital was run by the Department of Veterans Affairs, it was primarily war veterans that were treated there, and these were veterans or WW1 And WW2 ” Moczulski recalls. “A lot of those patients were hit with mustard gas during the war, which just destroyed their lungs.”

Treatments were limited, and the respiratory team focused on easing breathing and helping physicians test new therapies, including menthol-based nebulizer solutions. Physicians were always trying to improve the lives of veteran patients there and give them the care they deserved.

Dave also supported the War Memorial Children’s Hospital, where he and his colleagues cared for children with severe respiratory infections.

“We used to deliver oxygen tanks or croup tents via an underground tunnel under South Street, because a lot of kids had respiratory infections and had to be put in a tent just to be able to breathe properly,” he says.

Despite the intensity, those young patients stayed with him.

“The kids and the vets are the part of the job you don’t forget. To see the kids leave the hospital was a treat. With the vets, you had some that just struck home. You looked forward to seeing them and hearing their stories… it was a complete emotional education for me.”

Beyond the clinical world, he remembers the culture and the fun that helped shaped the hospital community. He fondly remembers the holidays, recalling, “A group of us used to meet at the Public Address system and sing carols to the patients while most departments decorated and painted their windows in the festive spirit.”

For him, the connection to the hospital was also quite personal.

“I was raised in the neighbourhood and lived across the street from Victoria Hospital on Colborne Street most of my childhood. As a kid, I had a paper route, and my morning papers got delivered to the front door of the old Victoria Hospital. A kind orderly used to sit there and help me fold my papers. We, as kids, also used to play down at the old pond near the river behind Victoria Hospital – those were some good memories.”

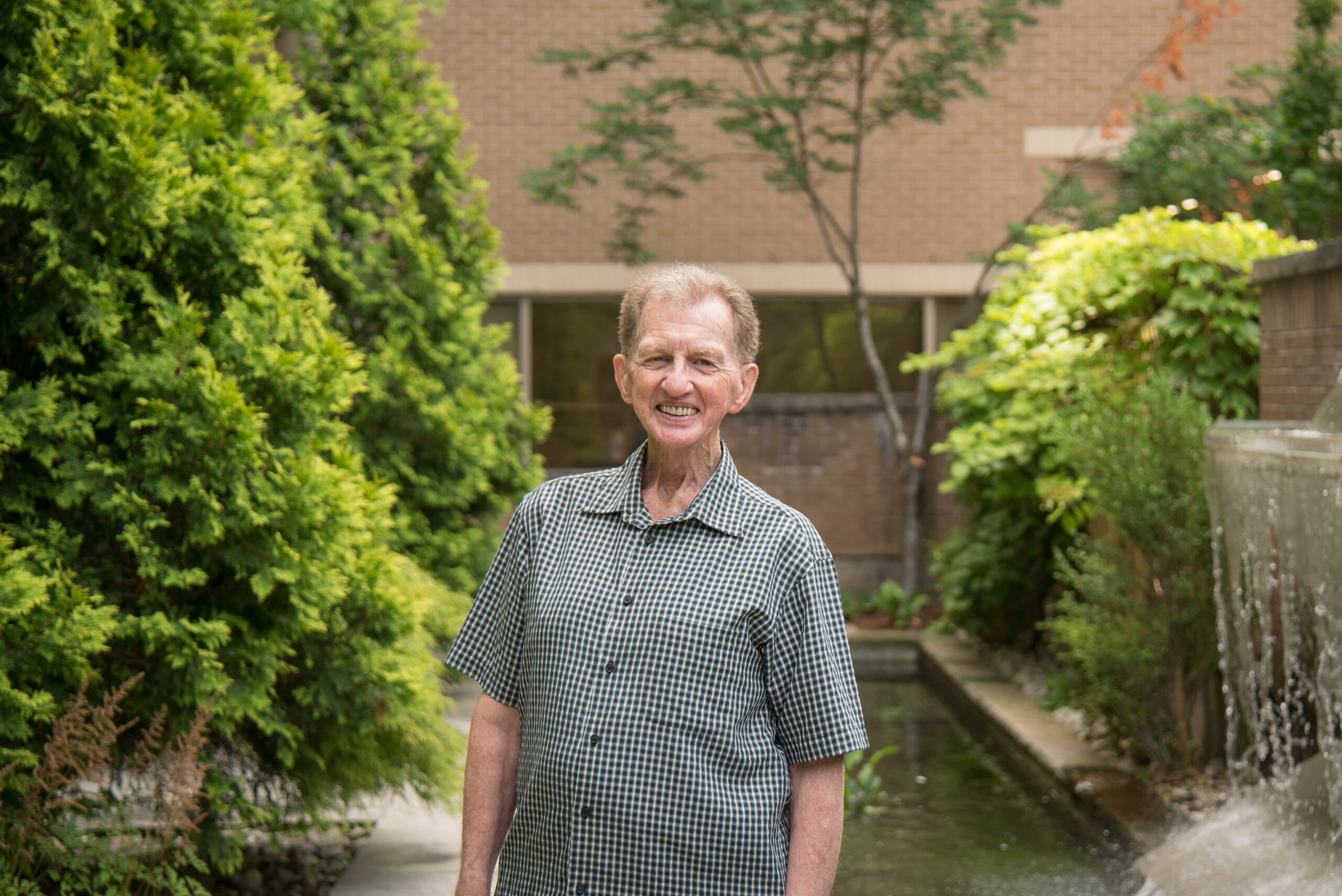

Today, respiratory therapy is an established profession with more than 12,000 practitioners across Canada. Its roots, especially in Southwestern Ontario, trace directly back to Victoria Hospital and the first six students recruited by Dr. Spoerel, which still matter deeply to Moczulski.

“When you look back on the history of the profession, a lot of it started at Victoria Hospital. Six guys out of high school, just ready to learn.”

His pride for those early days and his contribution remains strong as he reflects, “It had quite the impact. I think back and realize we were part of that. Now thinking that there are over 12,000 in Canada – it’s a big deal.”

Moczulski’s career reflects the heart of LHSC – patient care grounded in humanity, shaped by innovation, and carried forward by people willing to learn and adapt.

As LHSC celebrates 150 years, his story reminds us that behind every advancement, there are the people that helped build the foundation for the care we provide today.

LHSC is celebrating 150 years of care, innovation, and community impact by sharing 150 moments from our history. Join us in marking this milestone by sharing your own LHSC story.